In Dialogue with artist TJ Banate

synthesis by Charlotte Lombardo

photography by Jahmal Nugent aka @ninjahmal

Queering Place, is part of the Making with Place Public Art Projects of SKETCH for ArtworxTO: Toronto’s Year of Public Art 2021-2022. It proposes a tactile land-based and digital art installation weaving together natural and found materials, plants, medicines, and story with digital media inflections. It is envisioned as an inclusive community gathering space that welcomes and nurtures Queer, Trans and 2Spirit young people while critically and creatively exploring the roots of Queer* identity & ecology.

Gardening as tending to the physical, and the metaphysical.

At the core of the residency are six queer artists, who are trying to take care of ourselves, in spite of the times, [navigating impacts of multiple pandemics] and trying to take care of each other, and also trying to take care of an entire garden. From the beginning we needed to embrace fluidity, going with the flow, adapting to what shows up, adapting to what becomes available to us. Because there are things you can’t completely control, even if you are in control of some of things, some of the time.

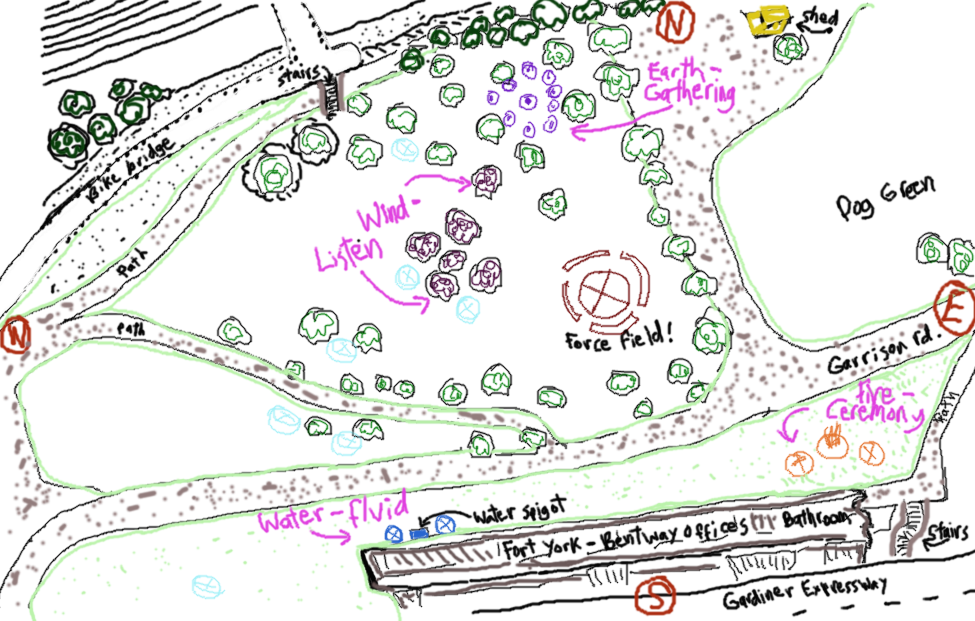

We started the residency without knowing where we were going to build the garden. And then when we settled onto the Garrison Common area, beside Fort York. This sparked much discussion. Historical associations with this colonial, military place, and all that this reflects and symbolizes. And reframing this as an invitation to heal a place that carries a lot of pain, and carries a lot of complex colonial histories.

On an ecological level, opening up to the teachings around us: noticing which trees are natural to these lands; noticing that the majority of the trees are not native species, and often were intentionally placed there because they don’t bear fruit, so they wouldn’t repopulate. So we began to explore the idea of the park itself as having been developed.

We built a medicine wheel garden, reintroducing Indigenous medicines, consciously connecting with the planters in a pollinator river, [which drew pollinators up from a southerly garden to the north east corner of the Commons] Little bunny babies were born in our sweet grass, protected from predators by the space that we had created. We learned to garden with tenderness and care.

We witnessed a change in how people began to navigate the space. People began to notice ‘this place is being taken care of’. The planters we installed, the medicine garden, the art pieces and activations. People started to navigate the space with a different kind of energy.

It is possible that radically different people can be in space with one another, and come out feeling like family.

As the residency grew, [engaging eight artists] and as Covid restrictions evolved and vaccination started rolling out, it became a form of community care to help each other get our shots. It became our way of caring for each other, and to feel even more safety in space with one another. All of the residents endup being each other’s social circle. The people we would actually see in person, every week, and be in space with. You have to trust one another, you have to know that we’ve got each other as priority, because otherwise you can’t do this kind of work.

People said the garden is like a beacon, there’s a gathering circle, there’s a fire. The real beacon was the care, the sense of love that you could feel as you walked in. You felt allowed to be there.

Politics of Place

Visitors talked about this being one of the first times they felt comfortable being in community, after the Covid lockdowns, which complicated our sense of bodies, and space and risk.

When we started the residency, the city was experiencing rising houselessness. For much of the residency, a housing encampment was actually growing near the site. The folks who were settled there almost became extensions of our residency. They were taking care of the garden when we were not there. They were helping to create place. It was a very unique situation, the space where we were planting and working was also where others made their home. So it was a learning experience.

Eventually the encampments were forced to leave. It really did feel like something was uprooted. There was something missing. These experiences sparked a lot of conversations around transformative justice. How can we be better? Complicated feelings about the fact that we we’re given permission to activate that space, where others were not allowed to. What gives a person permission to occupy space, what permits a person to be somewhere?

Question marks make way more sense than periods

As soon as you place a period on a place, on an idea, you limit, you define. You don’t allow it to be something more, or to develop into something different.

Queer experiences or lenses that we carry as individuals vary. Queer identities, two spirit, LGBTQ+, are constantly changing. We should never cling too closely or too tightly to pre-set ideas. Living organisms are constantly growing, shedding, changing. A tree sheds its bark, leaves, in order to strengthen. We need to make space for this within our communities. Creating place to re-experience and re-imagine our futures. Embracing fluidity, expressing a broader, more inclusive understanding of the social system that we’re trying to change.

Twinning fluidity and failure, a reclaiming, a celebration.

We talked a lot about embracing Queer Failure. Because life comes in. Growing things, in public space, you need to constantly revisit and restructure. Learning to work with a place, and listening to what it is asking of you, instead of trying to impose.

Accepting what comes. Especially in light of the current climate. You can only plan so far ahead. This intersects with queer politics and queer experiences. Many queer folks are blocked from planning very far ahead. Career, life plan, many folks are living paycheck to paycheck. Different marginalized experiences, your day to day already has that struggle.

Reclaiming, even celebrating, failure. You have to turn it around. Understanding how that experience planted the seeds for something better to grow. Embracing fluidity. Nothing changes if we are just sitting comfortably.

And I mean, how can you not embrace this, when you’re up on stage?

We need to challenge the colonial mindset and requirement to always measure change, measure impact. To create some body of data, or proof, that something is worthwhile.

What do you need to cast off to make room for growth and change?

On the surface level, we may not instantly see change. A lot of the work that we have done, what ended up manifesting in the residency, was very philosophical. Not always physically tangible. Initially, as a group we had hoped to do more physical elements, but there were tensions. We couldn’t do certain things with the land, because it wasn’t necessarily ours. And then when we did create physical things, people were not always well behaved. One of our planters got completely destroyed, and all six of us had to come together to fix it, put it back together again. So on a physical level, I think it’s not as obvious. But there are subtle ways. When we were there occupying space as a group, people would navigate the space a little differently. Even the dogs would start coming up to us, like ‘hey friends’.

We learned that by law you cannot disrupt Indigenous persons from holding sacred fire ceremony in public space. And that was information that none of us previously knew. And that impacts anyone who had anything to do with Queering Place. Even the city staff and people who helped us with access, who are witness to us navigating fluidity, red tape, weather, etc.

What we created is not necessarily very loud or very long lasting physical change, but it’s the social change that shifted. Even on an individual level, the artist residents have now created relationships, connected our communities through direct transfer of knowledge and wisdom. Queer spaces were opened up, resisting against structures that tell us how and what to know.

Prior to Queering Place, my ideas about community organizing were a lot more rigid than they are now. It doesn’t always have to be formally structured.

Can we just gather? Can we commit to showing up? Can we make space for what is wanting to be built? Can we prioritize just being in space with one another?